A Thai-Cambodian border dispute has made frequent headlines over recent weeks. Characterized by low-scale skirmishes for several weeks, the past few days alone saw a remarkable escalation of military tensions, including the discovery and explosion of land mines as well as mutual exchanges of fires, reportedly killing and wounding civilians and soldier on both sides. The developments lend renewed urgency to a dispute between the two neighboring countries whose border line has not yet been clearly demarcated.

In early June 2025, Cambodia officially declared to bring the dispute to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), so why does Thailand insist on diplomatic channel for the dispute resolution and strongly reject the ICJ jurisdiction over the dispute? The answer does not lie under Thailand’s unacceptance of the ICJ jurisdiction, but the colonial legacy constructed by France, the former protector of Cambodia during 19th century and the early 20th century. This post reveals that the construction of international law based on the standard of civilization perpetuates the legal impediment for the former semi-peripheral Siam (Thailand) in the border dispute with former protectorate Cambodia as the Franco-Siamese treaties intersect with the making of Siam as a modern nation-state.

The disputed areas and the ICJ decisions on the Temple of Preah Vihear

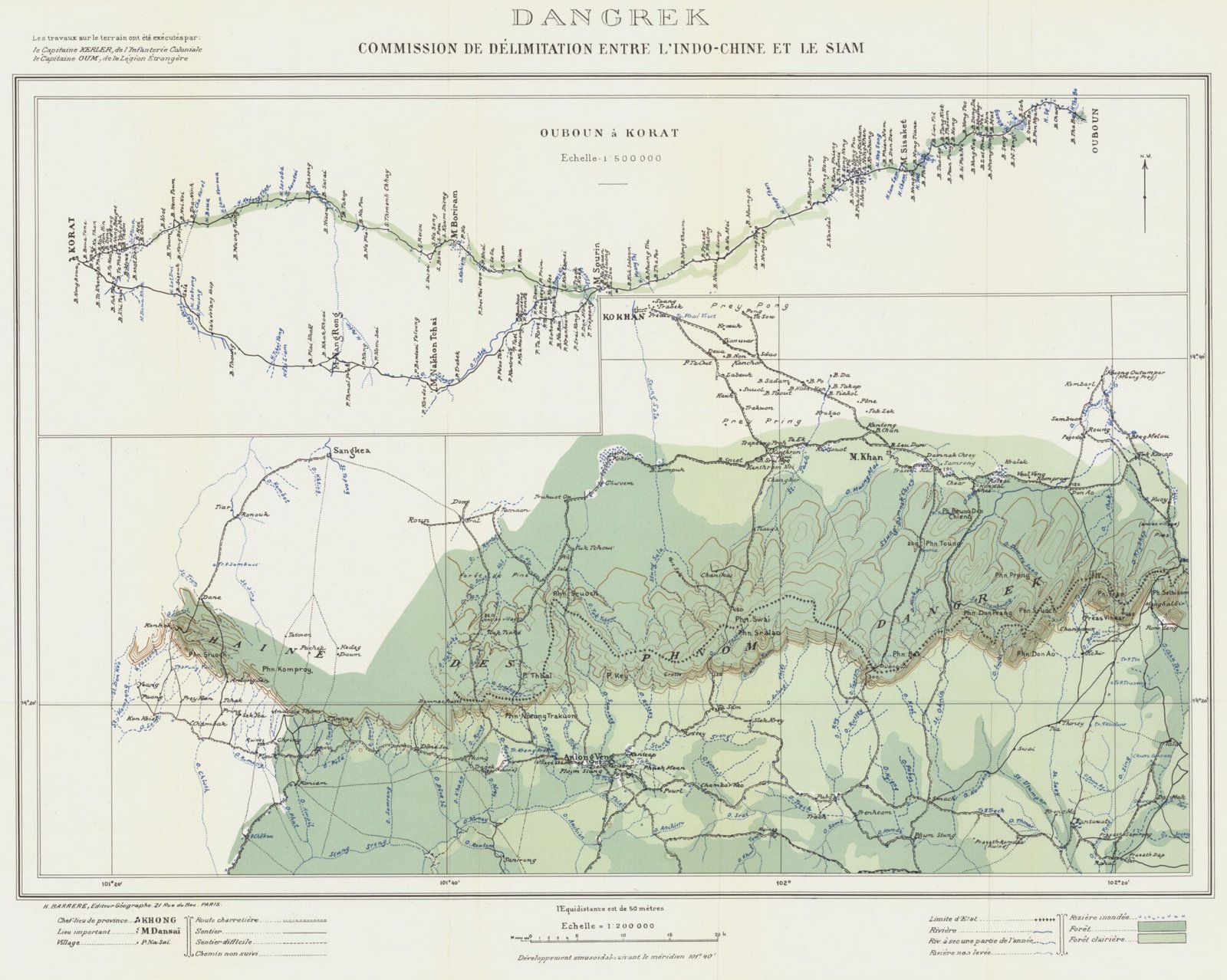

The reference to the ICJ ruling on the Temple of Preah Vihear in Cambodia’s statement on 15 June 2025 to submit the border disputes involving the Emerald Triangle, Ta Moan Thom, Ta Moan Tauch, and Ta Krabei Temples implies the Cambodia’s potential argument on the legality of Annex I map addressed in the Temple of Preah Vihear case. Dating back 63 years ago on the same date, the ICJ ruled that the Temple of Preah Vihear was situated in the territory under the sovereignty of Cambodia and Thailand was under an obligation to withdraw its military and police forces from the vicinity of the Temple, as well as, to return the artefacts removed from the Temple and its area to Cambodia. This ICJ decision relied upon the Annex I map which was allegedly claimed to be the product of the Mixed-Commission between France and Siam in charge of the delimitation of the boundary between Siam and the French Indo-China according to Article 4 of Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907. Although the Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1904, the predecessor of the 1907 Treaty, established the watershed line as the border division between Siam and Cambodia, Thailand was precluded from contesting the validity of Annex I map locating the Temple of Preah Vihear on Cambodia’s territory. The subsequent acquiescence on the part of Prince Damrong Rajanubhab, as Siam’s representative, has been interpreted as estoppel, thereby preventing Thailand from rejecting Annex I map, despite its deviation from the agreed watershed line. However, this ICJ decision overlooked the unequal power dynamics inherent in colonial diplomacy and cartography which challenged the legitimacy of such consent.

Despite the ICJ decision declaring that the Temple of Preah Vihear was under Cambodia’s territorial sovereignty, the dispute arose again in 2008 since the operative part of Temple of Preah Vihear judgment in 1962 did not clearly define the scope of the vicinity of the Temple and whether that vicinity was under Cambodia’s territory. The ICJ relied on Article 60 of the Statute of ICJ to interpret the operative part of the 1962 judgment and declared that the vicinity of the Temple including the entire promontory of the Temple forms part of Cambodia’s territory. However, the ICJ rejected Cambodia’s request for the pronouncement of the legality of Annex I map as the frontier line between Cambodia and Thailand.

The revisit of ICJ’s 1962 and 2013 judgments shows the role of Annex I map as evidence for Cambodia to delimit its border with Thailand as Annex I map, in its 1:500,000 scale, covers the Dangrek mountain range from Ubon Ratchathani to Nakorn Ratchasima provinces. Therefore, Annex I map, in general, could cover the Emerald Triangle located in Ubon Rachathani province and Ta Moan Thom, Ta Moan Tauch, and Ta Krabei temples located in Surin province. However, the ICJ’s unwillingness to pronounce the legality of Annex I map has removed the possible claim of Cambodia to rely on the legality of Annex I map as the basis to further request the ICJ to exercise the jurisdiction. Thailand has withdrawn its acceptance of ICJ jurisdiction in 1960. The ICJ jurisdiction was, therefore, limited to the interpretation of its judgment according to Article 60 of the Statute of the ICJ which restricts the scope of interpretation merely to the subject-matter of the dispute in the Temple of Preah Vihear judgment in 1962. The ICJ clearly indicated that the subject-matter of the Temple of Preah Vihear case concerned the territorial sovereignty over the Temple, not the delimitation of territory between Cambodia and Thailand.

The Semi-colonized Siam and her quandary

Annex I map was the fruit of imperial encounter between Siam and France. The series of treaties concluded between Siam and France, namely Montigny treaty in 1856, Franco – Siamese treaties of 1904 and of 1907, on the one hand, reflects the unequal sovereignty of Siam and on the other hand, transforms Siam’s concept of sovereignty from Mandala system to European territorial sovereignty. As Thongchai Winichakul wrote in Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation that Siam’s reliance on Mandala system depicting the shared and overlapped sovereignty without the clear-cut boundary was transformed to the defined territory through the contacts with the imperialists including France and the Great Britain. Articles VIII and XI of Montigny Treaty adopted the extraterritoriality model from Bowring Treaty concluded between Siam and the Great Britain in 1855. According to Article VIII of Montigny Treaty, when the dispute arose between French and Siamese subjects, the French Consul had the authority to settle the dispute. Article XI of Montigny Treaty imposed the application of the French law in the criminal charges against French subjects in the territory of Siam. Thus, these extraterritorial clauses evidently show the semi-colonized status of Siam whose territorial jurisdiction cannot be exercised over French subjects.

While being semi-colonized, the French motive to secure its colonies’ territory contributed to the realization of Siam’s defined territory. Articles I and II of Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1904 delimited the boundary between Siam and Cambodia, and Luang Prabang which were the protectorates of France. The special attention should be given to the relative similarity of Article III of Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1904 and Article IV of Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907 establishing the mixed-commission between Siam and France to demarcate the boundary. When read in conjunction with Article VII of Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907 affirming the continued application of provisions from the 1904 Treaty not expressly modified by the 1907 Treaty, it becomes clear that the mixed-commission should have demarcated the border between Thailand and Cambodia in accordance with the watershed line. This was one of the core arguments of Thailand during the Temple of Preah Vihear dispute as the frontier line between Thailand and Cambodia must have been determined by the watershed line, not Annex I map line.

Considering the semi-colonized status of Siam when concluding treaties with France, one could question why Thailand did not raise the argument of unequal nature of the treaty based on French imperialism, to reset the boundary between Thailand and Cambodia. The answer lies in two prominent aspects of the making of modern nation-state Siam.

First, the discipline of international law requires the defined territory as the basis of statehood. Siam could not shift from Mandala system to territorial sovereignty without reliance on European imperialists through treaties and cartography. As written by Antony Anghie in his famous book Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law (p.65), the positivist jurisprudence of international law excluded the non-European societies by the standard of civilization and readmitted them into international society only when they conformed to European international law. The undefined territory resulted from the revocation of treaties with France would have caused trouble to Siam when it was admitted to international society through joining the League of Nations in 1920.

Second, Franco – Siamese Treaty of 1907 represented a step toward the sovereign equality of Siam. Article V of the Treaty ended the extraterritoriality applicable to the Asian origin persons admitted as the French subjects. The extension of extraterritoriality asserted by France to the Asiatics created the conflicting jurisdictions and arbitrary law enforcement, obstructing the transformation of Siam to a modern nation-state. The gradual limitation of extraterritoriality illustrates Siamese attempt to fight the imperialism with the hope to become equal sovereign as her Western counterparts. If Franco-Siamese treaties of 1904 and of 1907 were to be revoked based on imperialism, it might affect the legality of other treaties concluded with France and other states, since the state-building of Siam was entangled with the colonial encounters.

Therefore, the unequal treaty argument was not an option for Siam during the Temple of Preah Vihear dispute with Cambodia. Nor is it in the current dispute. The reality of post-colonialism reveals different results for the former protectorate and the semi-peripheral Siam. Cambodia inherits the imperial mapping from France, whereas Thailand is trapped in the colonial legacy by not being able deny the binding force of the imperial map.

Conclusion

In the Temple of Preah Vihear cases of 1962 and 2013, the ICJ rendered its decisions based on a single section from 11 sections of Annex I map produced by the French surveyors. The scope of other sections of Annex I map could cover the area in the current dispute. If the current dispute is admitted before the ICJ, the pertinent questions are the following: how the ICJ will consider the validity of Franco-Siamese Treaties of 1904 and of 1907, as well as, other sections of Annex I map; and whether the line in Annex I map should become the treaty settlement binding upon Cambodia and Thailand, despite its divergence from watershed line. These two questions might not be resolved through the mere treaty interpretation rules under Articles 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) 1969. The central legal issue lies in the enduring colonial legacy that upholds the binding force of imperial treaties and cartographic representations. It remains to be seen whether the ICJ will consider the legal sensitivities of Thailand’s historical status as a former semi-periphery in its interpretation of treaties governing the current territorial dispute with Cambodia.

Author

Dr Papawadee Tanodomdej is an Assistant Professor of International Law at the Faculty of Law, Chulalongkorn University, in Bangkok.