International Law in Asia Today is a new blog series launched by AsianSIL Voices to highlight historical events that mark Asia’s engagement with international law. Each post revisits a specific date to make international legal history in Asia more visible and accessible to a wider audience.

This Day in History

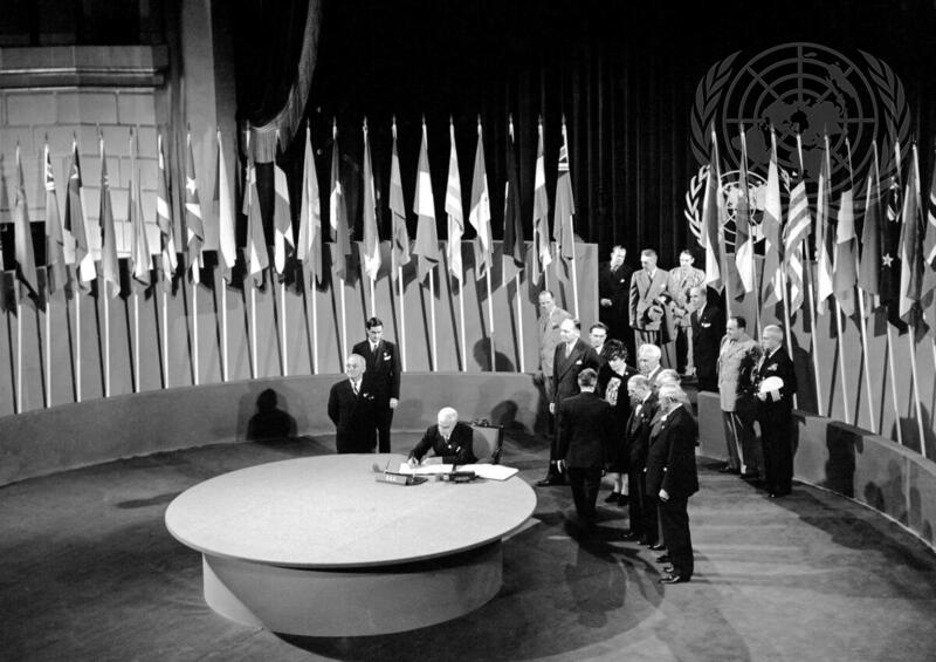

On the 24th of October 1945, the UN Charter entered into force, after its ratification by the 5 permanent members of the Security Council. Merely 7 months before, 50 states had come together at the San Francisco UN Conference on International Organisation to create this Charter, now hailed as a uniting force “in the pursuit of peace, security, development and human rights”. However, among the 50 flags present, merely 8 Asian flags fluttered. 80 years on, 25% of the UN membership consists of Asian states. How has Asian participation in the United Nations evolved across these 80 years and how might it continue in the future?

Early Asian Participation

Asia’s performance during the San Francisco Conference was limited with only 38 proposals out of 547 submitted by Asian states. Among these 8 states, India and the Philippines were not even independent yet, despite the UN’s founding principle of “sovereign equality of all its Members”. The Arab states did not voice out any concerns and while Iran tried to introduce proposals, they were all rejected. Even on pressing issues that pertained to them, such as the maintenance of international peace, Asian states submitted just 3 proposals out of 136, all of which were rejected. Nevertheless, some amendments provided hope – the passing of one Chinese and one Indian amendment was instrumental in the development of articles 13 and 19, showcasing the potential of Asian contribution.

Despite their under-participation, Asia learnt 2 lessons – 1) the UN was an important platform to develop their international influence, 2) they could use the Great Powers to further their national agendas. However, in doing so, Asia’s participation was only limited to issues that were of direct national interest and they neglected to focus on issues of international importance such as disarmament.

Prominence of the Asian View

In the post-World War II era, especially during the Korean War, Asian states became increasingly aware that they could not remain solely self-interested. The problems of Asia would soon lead to global consequences. Therefore, there was a need to move away from their narrow conception of international law.

The formation of the Afro-Asian Group allowed Asian states to discuss paramount international issues without having to agree on policy formulations. This group also pioneered the novel foreign policy stance of non-alignment. Previously, countries felt the need to side with either one of the Cold War powers in order to receive more economic aid. However, a separation from these Great Powers did not preclude them from receiving such. As Ambassador Burudi Nabwera aptly summarised, “Hitherto, neutrality had meant a withdrawal from the conflict… But since the advent of positive neutrality the situation has changed.” Its influence was seen in the adoption of the draft resolution which condemned all nuclear-weapon tests. Most crucially, the support of non-aligned countries was best observed during the settlement of the Prisoners-of-War issue during the Korean War. India’s non-alignment to either Cold War power allowed it to comprehend each country’s stance accurately, providing a third option that had not been contemplated by either nation. This was widely hailed as the first manifestation of “Asianism”.

Present Issues

Compared to the formative years, Asian participation in the United Nations has increased with Asian states constituting 25% of the UN membership. Asia has maintained its bid at international influence by playing a significant role in peacekeeping. Additionally, it contributes considerably to economic development. Instruments such as UNCLOS and Law of self-determination also reflect Asia’s contributions to international law.

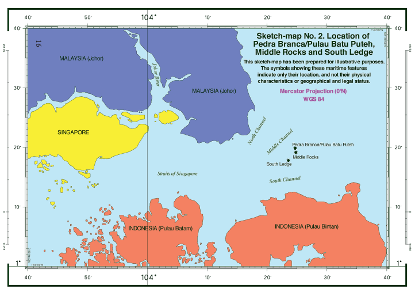

However, Asia remains ambivalent towards international law. Despite accounting for nearly 60% of the world’s population, Asia’s representation in international organisations is devastatingly low. Might Asia’s commitment to sovereignty be at odds with the notion of an international community? Given colonial histories and experiences such as the Tokyo Trials and Unequal Treaties in China, Asia tends to deal severely with encroachment of sovereignty. Therefore, in line with “Asian values”, Asian states tend to prefer informal dispute resolution mechanisms via bilateral negotiations. This is seen most prominently in the ASEAN Way governed by the principles of non-interference and peaceful consensus that guides ASEAN’s approach to international law. Another obstacle appears to be the lack of a common identity across the Asian continent since Asian Values cannot represent the diversity of values across every Asian state.

Looking to the Future

The role of Asian states in the United Nations seems to have evolved past acquiescence but they continue to navigate the global order as simply “rule-takers” rather than “rule-makers”.

The UN was most active and efficient when the United States was “the only superpower”, which allowed for easier decision-making. However, as we enter an increasingly multi-polar era in which “Asian states [may] gradually [take on] a more prominent role”, this pressing question emerges – might there be a convergence or divergence of Western and Asian interests?

Conventions such as UNCLOS point towards the unique adoption of peaceful dispute settlement measures that align more with Asian interests, signalling a move towards Eastphalia. On the other hand, recent responses to the Rohingya conflict, reframed by Malaysia as a “regional concern”, suggest a shift away from non-interference, showing Westphalia might be here to stay.

These developments remind us that international law is a dynamic phenomenon that adapts to changes in the global order. It remains to be seen how Asia’s continued engagement with the United Nations will impact not just Asia, but the future of international law.

Author

Manya Sethi, Year 2 LLB (Hons.) Student, NUS Law

Image credits: https://media.un.org/photo/en/asset/oun7/oun713031